Earlier this week, Jimmy Carter, the 39th president of the United States, died at the advanced age of 100. The outpouring of tributes to Carter as news of his death broke reflected his great popularity. Though he was despised by the right-wing during his presidency, in retirement Carter became one of the most beloved and respected ex-presidents, embraced by liberals and conservatives alike.

Carter was eulogized by the current president and fellow Democrat, Joe Biden, in the most glowing terms:

Jimmy Carter stands up as a model of what it means to live a life of meaning and purpose, a life of principle, faith and humility. What I find extraordinary about Jimmy Carter though is that millions of people all around the world, all over the world, feel they lost a friend as well, even though they never met him.

Similar eulogies rolled in from across the political spectrum, with many voices on the left joining in praise of Carter. Later in life, Carter became something of a progressive saint thanks to his famous advocacy for the poor and homeless and his leftward-shifting positions on Palestine and LGBTQ+ rights. Left Action’s statement on Facebook typifies this kind of uncritical progressive support for Carter:

For a century, he was a shining example of what it means to be a truly good and decent human being. People across the nation and the globe loved and respected him, and with good reason. Please join us in thanking him one more time.

The true meaning of presidential eulogies

Amid all of these flowery tributes, it’s important to be aware of what is actually being communicated. Honoring ex-presidents living or dead means honoring the office of the presidency, along with other institutions of the US political order including the slaveholders’ Constitution. It is a way for the eulogist to signal support for US political “norms” and for the status quo.

Dead presidents are inevitably praised for their statesmanship, their humanity, and their faithful service to the Constitution and to the US. Their failures and foibles are excused, and the long-term consequences of their policies for the working class and the oppressed, the Global South, and the environment are ignored.

Presidents whether Republican or Democrat serve the capitalist order. This is why it is crucial for leftists to be critical of presidents — even in death, even when they were “good and decent” people.

Liberal politicians and pundits even praised Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan upon their passing in 1994 and 2004 respectively. Both were among the staunchest enemies of liberalism during their careers, but all is forgiven in death.

In turn, just look at how the conservative National Review praised Carter this week:

He put missiles in Europe to defy Soviet buildups and bolster the NATO alliance. He brokered peace between Israel and Egypt. He installed Paul Volcker, the man who finally broke inflation, as chairman of the Fed. He approved an audacious plan for rescuing American diplomats held hostage.

Thus, eulogies of dead presidents shed light on the nature of the bipartisan political order in the US. During an election year, the differences between Republicans and Democrats are presented as a vast and unresolvable conflict. This conflict is always smoothed out when a president dies — just as it is always smoothed out in bipartisan support for US imperialism.

More broadly, presidential eulogies play an important role in reinforcing bourgeois ideology. Presidents whether Republican or Democrat serve the capitalist order, which is the ultimate basis of their unquestioning veneration by the media and politicians. This is why it is crucial for leftists to be critical of presidents — even in death, even when they were “good and decent” people. Every US president is our class enemy.

Jimmy Carter, founder of neoliberalism

In his time in office from 1977 to 1981, Carter served as a transitional president during a pivotal epoch in US history. The world plunged into economic crisis as the long postwar boom finally ended. The US had just lost the Vietnam War under Carter’s predecessors, Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford.. In the wake of these shocks, and to better compete with Germany and Japan, the capitalist class in the US sought to reassert its military and economic might.

The result was a new set of policies that would come to be known as neoliberalism. This meant cutting taxes on the rich, attacking unions to increase the rate of exploitation, deregulating industry, privatizing public services, and slashing social programs. Similar policies were instituted in the United Kingdom under the newly formed Margaret Thatcher government.

Carter accommodated these agendas on all fronts. He raised the US military budget by 10 percent a year, and engaged in a massive deregulation campaign while cutting social programs. He showed his allegiance to capital over labor, using the repressive Taft-Hartley Act against the United Mine Workers in 1978. As Jacobin put it in one of several refreshingly blunt assessments of Carter’s presidency:

His pro-business bent led him to deregulate the trucking industry, the airlines, the railroads, and natural gas prices. This restored profit for corporations but led not to job growth but mass layoffs for the unionized workers in these industries. The consequences of this handiwork are still with us today.

As William Wippinsinger, then president of the International Association of Machinists said about Carter: “It’s quite clear he marches to the drum beat of the corporate state.”

Carter’s administration actually created the plans for one of Reagan’s most infamous actions: the vicious busting of the air traffic controller’s strike in 1981.

Much of what Reagan is reviled for, Carter did first. While Reagan and Thatcher are popularly blamed for the onset of neoliberalism, Carter’s innovative role in laying the groundwork for the current economic order is severely underrated. The most striking example of this is that Carter’s administration actually created the plans for one of Reagan’s most infamous actions: the vicious busting of the air traffic controllers’ strike in 1981.

Behind these actions was clear intent expressed by his close advisors. Carter’s “Inflation Czar” Alfred Kahn, a self-described “good liberal Democrat” was blunt about his goals:

I’d love the Teamsters to be worse off. I’d love the automobile workers to be worse off. I want to eliminate a situation in which certain protected workers in industries insulated from competition can increase their wages much more rapidly than the average.

In a 2012 letter to Socialist Worker, Gary Lapon summarized the Carter administration’s neoliberalism well:

Carter appointed Paul Volcker, Jr. as Chairman of the Federal Reserve. In 1979, Volcker said that “the standard of living of the average American has to decline.” His solution to the crisis of the 1970s was to jack up interest rates, which triggered a recession that saw unemployment rise, laying the ground for big business to attack unions and drive workers’ living standards down to increase the rate of profit.

Carter’s catastrophic foreign policy

Carter’s foreign policy served American imperialism just as his domestic policy served American capitalism. He supported dictatorial and murderous regimes all over the world, including the Philippines, Iran, Nicaragua, and Indonesia. Sherry Wolf detailed the Nobel Peace Prize-winning president’s record of war-making in a 2002 article for International Socialist Review, which is worth quoting at length:

Most of the hundreds of thousands of deaths in East Timor took place during the Carter administration, which increased military aid to the Indonesian dictator Suharto by 80 percent. In Zaire, Carter sent the U.S. air force to ferry Moroccan troops to put down a popular uprising against the brutal dictator, Mobutu Sese Seko. He echoed Corporate America’s opposition to sanctions on the apartheid South African regime and vetoed UN Security Council resolutions that attempted to stop supplies to the racist military by U.S. companies. Carter ignored pleas from Salvadoran archbishop Oscar Romero to stop arms shipments and advisers to the junta there that was massacring trade unionists and human rights workers—and he continued arms transfers even after the junta brutally murdered Romero. In a move that would come back to haunt the U.S., he sent military and economic aid to strengthen the Islamic fundamentalist opposition to Soviet troops in Afghanistan. During a state visit in 1977, Carter toasted the Shah of Iran, calling him an “enlightened monarch who enjoys his people’s total confidence.” Two years later, the Shah’s forces fired upon thousands of protesters at the start of the revolution that threw him out of power.

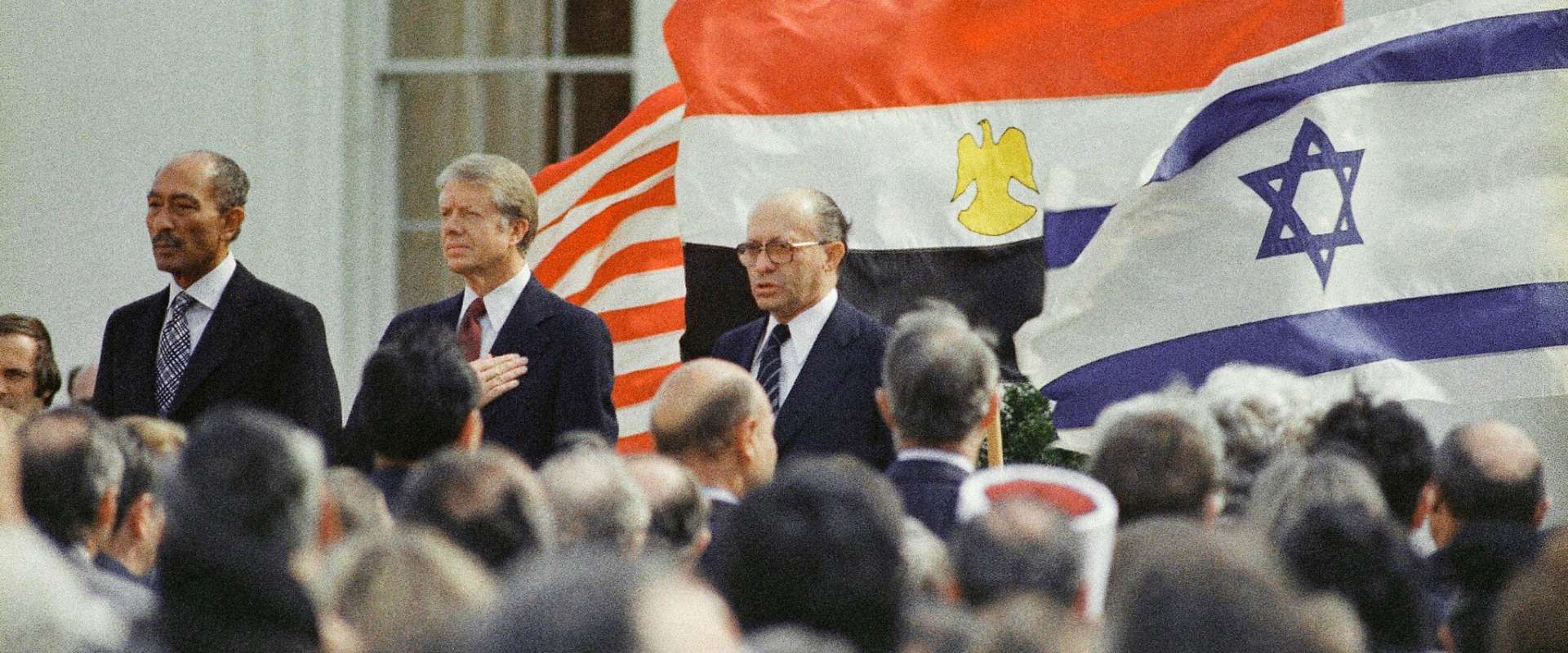

Carter is perhaps best remembered for brokering a peace deal in the Middle East that led to Israeli forces pulling back from occupied Sinai. What is forgotten is that in exchange Egyptian president Anwar Sadat accepted billions in funds as America’s closest ally in the region after Israel. Calls for a Palestinian state were rejected, and instead Carter dramatically increased aid that went toward Israeli settlements in the Occupied Territories.

In 1979, Carter signed Presidential Directive 59, establishing plans for fighting a “limited nuclear war, including a first strike policy.” Announcing the new “Carter Doctrine” in his 1980 State of the Union Address, Carter warned, “An attempt by any outside force to gain control of the Persian Gulf region will be regarded as an assault on the vital interests of the United States of America, and such an assault will be repelled by any means necessary, including military force.” In the wake of the Shah’s fall, Carter was instrumental in developing the Rapid Deployment Force, capable under the new doctrine, of intervening to protect U.S. interests in the Middle East.

U.S. imperialism was seriously wounded in Vietnam—the beast had been beaten and needed to recover from domestic disillusionment and international disdain. If at times Carter pulled back from more overt military action, it had nothing to do with his supposed pacifism. Nothing about the fundamental dynamic of economic dominance by the U.S. had been altered. American multinational corporations in the late 1970s were more active internationally than ever before, and any personal abhorrence he might have had about the killing in Vietnam never amounted to aid for that country to rebuild. The human rights reforms Carter verbally pressed for in South Africa and Latin America never threatened commercial dealings with these nations that supplied the U.S. with 100 percent of industrial diamonds, coffee, and rubber.

Carter covered his foreign policy with the rhetoric of human rights, but his concern did not extend to the people oppressed by US allies such as Iran, Israel, and El Salvador. Instead, the concept of “human rights” was a cudgel for Carter to use in a new phase of the Cold War against the Soviet Union. This included sanctions against the Soviet state, new missiles in Europe, and a boycott of the 1980 Olympics over the Russian invasion of Afghanistan. Worse, it also meant increased military spending and a reimposition of draft registration (“selective service”) for the first time since the Vietnam War.

Carter covered his foreign policy with the rhetoric of human rights, but his concern did not extend to the people oppressed by US allies such as Iran, Israel, and El Salvador.

Carter’s place in history

Taken together, Carter’s legacy was the beginning of Reaganism. He cut social programs, increased the military budget, pursued military competition with the USSR, and institutionalized neoliberalism. Just as McCarthyism actually started with the anti-communist program of Harry Truman, Reaganism started with Carter.

Carter did all this with a broad smile and apparent personal humility. He called for peace in Palestine but in reality helped normalize Zionism through the Camp David Accords between Israel and Egypt. His supposed advocacy for peace and human rights fooled far too many.

Those who want to overthrow capitalism and imperialism must overthrow bourgeois ideology along the way to that goal. One aspect of bourgeois ideology is presidential hagiography.

Carter’s humanitarian legacy was reinforced by his actions after leaving office. His Carter Center professed to support free elections around the world. He continued to promote Palestine — by encouraging Palestinians to accept their dispossession. He worked with Habitat for Humanity to build houses for poor people — many of whom lost their homes due to his austerity policies.

Capitalism pretends to favor freedom. Imperialism says it stands for free trade and development. We know this is just ideology. By the same token, Carter said he supported human rights, but we have to look at the true legacy that lies beneath the image of a “good and decent” man with a hammer in his hand.

Those who want to overthrow capitalism and imperialism must overthrow bourgeois ideology along the way to that goal. One aspect of bourgeois ideology is presidential hagiography. Just as revolutionaries do not vote for our enemies, the representatives of the capitalist class, we do not give them a pass because of smiles and nice words.